What is behind the AI revolution? The adoption of large language learning models (LLMs) in science is growing at a remarkable pace, and for good reason. Possibilities abound as LLMs are developed for a wide range of applications, from the design of novel viral genomes, the parsing of medical images for diagnostic details, and expedited drug development. But as many are coming to realize, the potential of AI is exactly that: potential. Converting the idea of AI into real, tangible benefits requires researchers to move beyond the computational domain and enter the familiar space of a wet lab.

Earlier this year, I attended the Nucleate Summit in Boston, Massachusetts, where leaders and students from around the biotech community came together to discuss the industry’s emerging trends, including a panel focused on the potential of automation and AI. As a participant in that panel, I was ready to defend my viewpoint that much of AI’s potential will wither in the absence of a wet lab feedback loop.

But no defense was needed. Instead, my colleagues from Oracle, Deep Origin, NewCo, Pillar VC, and I had a lively discussion about the necessity of bridging in silico and in vitro environments and what steps are being taken to do exactly that.

The Critical Nature of The Wet Lab

For all of its strengths, at the end of the day, AI is just another computational tool—albeit a powerful one. It can design new therapeutic antibodies, but it cannot synthesize them. It can highlight where genetic editing is most likely to have a desired effect, but it cannot assemble the necessary CRISPR constructs. In other words, AI is a tool that augments, rather than replaces, the wet lab. It can help us navigate biological noise, guiding us on a more direct path to answers. But, acting on that guidance with the same level of accuracy is a significant challenge.

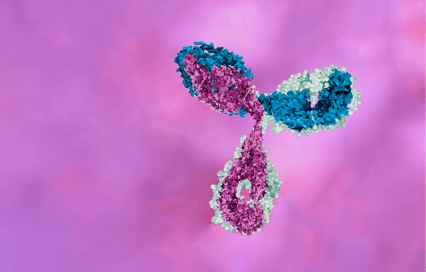

Consider the potential use of AI in optimizing therapeutic antibodies.

Antibody properties (such as target specificity, binding affinity, and stability) are dictated by complex intramolecular interactions. The process of optimizing these properties has historically involved the creation of vast screening libraries containing millions of related antibody variants. Even the largest screening libraries represent a small sample of the potential number of variants that could be tested. To be anything more than lucky, researchers must develop a rationale for selecting which variants to test and which to leave behind.

"Actually synthesizing AI-designed antibodies is not trivial"

AI can significantly improve this process, helping researchers rationally design screening libraries that are not only enriched for high-potential variants, but are often much smaller and less costly to assess. However, actually synthesizing the AI-designed antibodies is not trivial. Traditional DNA synthesis technology is limited to producing 150-300bp fragments, well below what’s needed for variant antibody domains. Accordingly, researchers must go through the error-prone process of stitching DNA fragments together to build each unique antibody, a task that may over- and under-represent certain sequences (that’s to say nothing of synthesis errors). At best, these imperfections can mean wasted time and resources as unintended variants are tested. At worst, they can mislead researchers.

All of this is to say that translating AI’s precise designs into the laboratory is not a simple process; whether it's for antibody development, CRISPR screening, or other such applications, it requires technological advances across the research enterprise.

Twist Bioscience is taking many steps to help researchers with this challenge. The advent of our Multiplex Gene Fragments, for example, enable the scaled production of custom DNA fragments up to 500bp in length. This makes it possible to directly synthesize entire antibody complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) with high accuracy. Such precision means AI-designed antibody variants can be synthesized with fewer errors and can empower a more efficient optimization process.

Feedback Loops

Twist Chief Scientific Officer, Biopharma, Colby Souders on stage among Nucleate panelists.

Twist Chief Scientific Officer, Biopharma, Colby Souders on stage among Nucleate panelists.

A key theme that surfaced in our panel discussion was that advances in wet lab technology are necessary, but so too are feedback loops between in silico and in vitro environments.

This is necessary because AI and machine learning (ML) technologies are often asked to make complex extrapolations from imperfect training data. Here, too, antibody optimization is a good example. A common challenge that researchers face is finding an optimal balance between competing properties. Changes to the antibody sequence that improve one property may detract from another. Historically, the optimization process has focused on the stepwise improvement of individual properties.

AI and ML can help researchers take a more comprehensive approach by predicting the combination of changes that are most likely to balance antibody features, enabling simultaneous optimization. Not only does this save time, but it is likely to produce overall better variants. However, these algorithms are trained on limited data sets that each focus on individual properties. As a result, many AI-designed screening libraries over-index on a single property, forcing researchers to still go through additional and costly rounds of optimization.

In other words, the potential of AI is undermined by limited training data sets. One way to overcome this is to establish a feedback loop, in which AI-predictions are put to the test in a wet lab and the resulting data is used to refine the AI’s training. This was recently done by researchers at a leading biotechnology corporation. By adding experimental feedback into ML training data, the team transformed its antibody design process from a static prediction task into an active learning problem where each round of testing informed the next. The result was a much more efficient path to antibody optimization.

Some laboratories index more on computational power and are less equipped for wet lab validation. Fortunately, the industry is evolving to support these labs. For example, Twist now offers more than just DNA synthesis. Researchers who lack the time or equipment for antibody characterization can enlist Twist’s help. We can now leverage our expertise and infrastructure (built for automation and scale) to produce large panels of antibody candidates and validate them in characterization assays for binding, affinity, immunogenicity and developability properties. The ability to seamlessly transition from sequence to data can be essential as more labs seek to bridge the gap between in silico and in vitro environments.

Souders and co-panelists at the Nucleate Summit

Recommended Resources

Subscribe to our blog

- Terms & Conditions

- Policy on Unsolicited Submissions of Information

- Privacy Policy

- Regulatory and Quality Information

- Security

- Payment Information

-

© 2025 Twist Bioscience. All rights reserved.