Optimizing biologics for in vivo imaging

Visualizing molecular processes is difficult. It’s exponentially harder when the processes are buried underneath dense, heterogeneous layers of living tissue. But tracing the movements of specific cells or proteins in the human body could dramatically improve our ability to diagnose and treat disease.

Rendering small details visible isn’t the hard part. For centuries scientists have peered into the molecular world through the use of microscopes and an arsenal of fluorescent, luminescent, and otherwise colorful probes. It’s now routine in the research setting to use conjugated antibodies to tag specific proteins or cells with identifiable markers.

Yet, these tried-and-true methods are less reliable when it comes to in vivo imaging. Their long half-life in the body can be problematic when conjugated with radioactive isotopes that are typical in modern whole-body-imaging techniques. This means that imaging resolution is often poor as weak radioactive emitters need to be used to ensure an appropriate radioactive dose is received.

Fortunately, one alternative biologic with great potential is the affibody—a synthetic protein that is 20x smaller than an antibody that can also be engineered to have a short half-life, and to bind a wide variety of targets with high specificity.

Like any biologic, researchers developing affibodies have to go through optimization processes that involve iterative engineering of affibody variants and screening them for desirable properties.

🔎 What is an affibody?

An affibody is similar in function to an antibody in that they both bind with affinity to other molecules, but affibodies are much smaller. The average antibody is about 150 kDa, while the average affibody is only about 6.5 kDa. Affibodies contain a three-helix bundle domain and are based on protein A from Staphylococcus aureus, a virulence factor that binds human IgG. They can be engineered to bind many other molecules of interest

A recent paper from leading affibody scientist Professor John Löfblom of the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, highlights how soft-mutagenesis—a technique for altering protein function—can be leveraged to discover developable affibodies for imaging1. Using Twist Bioscience’s combinatorial variant libraries (CVLs), Löfblom’s team was able to engineer a rapidly cleared, high-affinity affibody targeting the cell surface protein CD69 to observe in vivo immune responses with remarkably low background noise.

Soft mutagenesis helps optimize affibody binding affinity

Löfblom’s team had previously identified a CD69 targeting affibody that was a promising candidate for imaging applications due to its rapid clearance, but had weak binding affinity2. To improve the affibody’s imaging resolution, the team took an engineering approach known as soft mutagenesis to increase binding affinity.

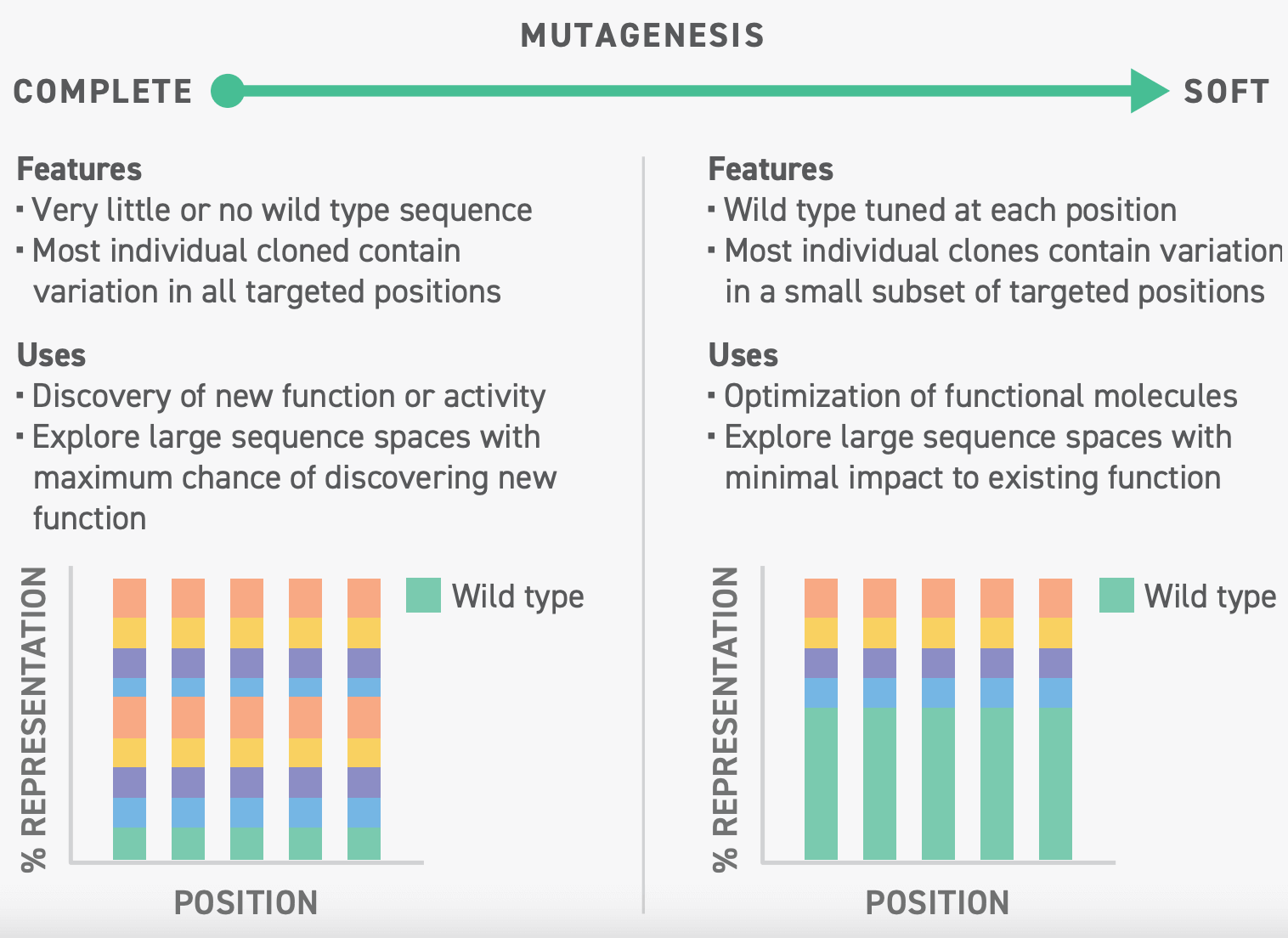

Soft mutagenesis is a technique that allows researchers to enhance desirable functions in a protein. Unlike complete mutagenesis wherein libraries are designed to maximize the number of mutations in each sequence, a soft mutagenic library is typically designed to ensure that each sequence is nearly identical to the parent sequence, save for a few mutations.

Through soft mutagenesis, Löfblom and his colleagues could methodically test which affibody mutations would affect binding affinity to CD69. To do this, Löfblom’s team leveraged Twist Bioscience’s CVL technology, enabling them to identify affibodies with improved binding affinity and favorable pharmacokinetic profiles.

Twist Bioscience offers a robust and efficient CVL platform that is capable of precise soft mutagenesis for the optimization of protein properties. Each variant is printed base-by-base and screened prior to synthesis, eliminating stop codons, liability motifs, unwanted mutations, and any undesirable biases, all at the beginning of the process. As a result, the library is enriched for the requested functional variants and the screening burden is reduced.

Put another way, with a Twist Bioscience CVL, researchers can be confident that the library they design is the library they’ll get, saving them screening time and resources. As we see in Löfblom’s work, soft mutagenesis can be a powerful way to improve biologics like affibodies and bring us closer to better in vivo imaging, you just need the right tools to make it happen.

Read more about affibody optimization here: Enhancing the Therapeutic Properties of a Cancer-Targeting Affibody by Soft Mutagenesis with Combinatorial Variant Libraries.

References

- Persson, Jonas, et al. “Discovery, Optimization and Biodistribution of an Affibody Molecule for Imaging of CD69.” Scientific Reports, vol. 11, no. 1, 27 Sept. 2021, 10.1038/s41598-021-97694-6.

- Andersson, Ken G., et al. “Autotransporter‐Mediated Display of a Naïve Affibody Library on the Outer Membrane of Escherichia Coli.” Biotechnology Journal, vol. 14, no. 4, 25 Sept. 2018, p. 1800359, 10.1002/biot.201800359.

What did you think?

Like

Dislike

Love

Surprised

Interesting